An “acceptable” similarity score isn’t one magic percentage; it depends on assignment type, citation practices, and how the report’s filters are configured. Low numbers can still hide improper copying, and higher numbers can be legitimate if quotes and references are included. Read the matches, not just the percentage, before deciding.

Table of contents

- What a similarity score actually measures

- What percentage is “acceptable”? Common ranges and context

- How filters and settings change the number

- Step-by-step: interpreting a report like an instructor

- Reducing high similarity ethically (without over-paraphrasing)

1) What a Similarity Score Actually Measures

A similarity score is a match percentage between your text and material in comparison databases, which typically include web pages, journals, previous submissions, and institutional repositories. The number is a quick signal, but it is not a verdict on misconduct. Similarity is not the same as plagiarism. It is a surface-level indicator of how much of your writing resembles other texts; the interpretation depends on why the matches appear.

Several common and legitimate features can raise similarity without implying wrongdoing:

- Quoted material that you have clearly marked and attributed.

- Reference lists, bibliographies, and titles that naturally repeat standard wording.

- Technical definitions and set phrases in scientific and legal writing that cannot be rephrased easily.

- Prompts, rubrics, or templates assigned by an instructor that all students reused.

On the other hand, a low score doesn’t guarantee originality. Patchwriting—replacing words with synonyms while keeping source structure—can slip under the threshold if the tool doesn’t flag paraphrases strongly. Likewise, matches may be spread across many tiny fragments that look harmless on their own but indicate over-reliance on sources. That is why the match list and context windows matter more than the headline percentage.

Think of the similarity score as a dashboard warning light: it tells you to look under the hood. The real decision rests on the patterns—where the text came from, how it is integrated, and whether appropriate citation and synthesis are present.

2) What Percentage Is “Acceptable”? Common Ranges and Context

Policies differ by institution and even by assignment. A literature review with numerous quotations may accept a higher baseline than a reflective essay that should be primarily in your voice. With that caution in mind, the ranges below summarize typical interpretations many instructors use as starting points—not universal rules.

| Similarity range | What it often indicates | Suggested action |

| 0–5% | Very low overlap; typical for original writing with minimal direct quotation. | Usually acceptable. Still scan matches to ensure key terms or titles aren’t incorrectly copied. |

| 6–15% | Normal for essays with a few brief quotes or common phrases; references may be included. | Likely acceptable if matches are properly cited and dispersed. Review any single passage with long, uninterrupted overlap. |

| 16–25% | Noticeable overlap; typical for research papers with longer quotations or extensive background sections. | Examine sources and integration carefully. Confirm quotes are block-formatted where required and that paraphrases truly reframe ideas. |

| 26–40% | High overlap; may signal over-quotation, patchwriting, or template reuse. | Rework sections to increase synthesis in your own words; add or correct citations; consider restructuring. |

| >40% | Very high overlap; often unacceptable unless the task is inherently formulaic (e.g., legal filings with stipulated clauses). | Substantial revision required; consult instructor or writing support before resubmission. |

Context is decisive. Some disciplines rely on standardized language (lab methods, statutes, diagnostic criteria). If quotes and references are excluded by filters, even a 10–15% score could reflect substantive copying; if they are included, the same number may be perfectly reasonable. Similarly, short assignments can show disproportionately high percentages from a single quoted paragraph. The better question than “Is 15% OK?” is “Is the overlap justified, cited, and proportionate for this task?”

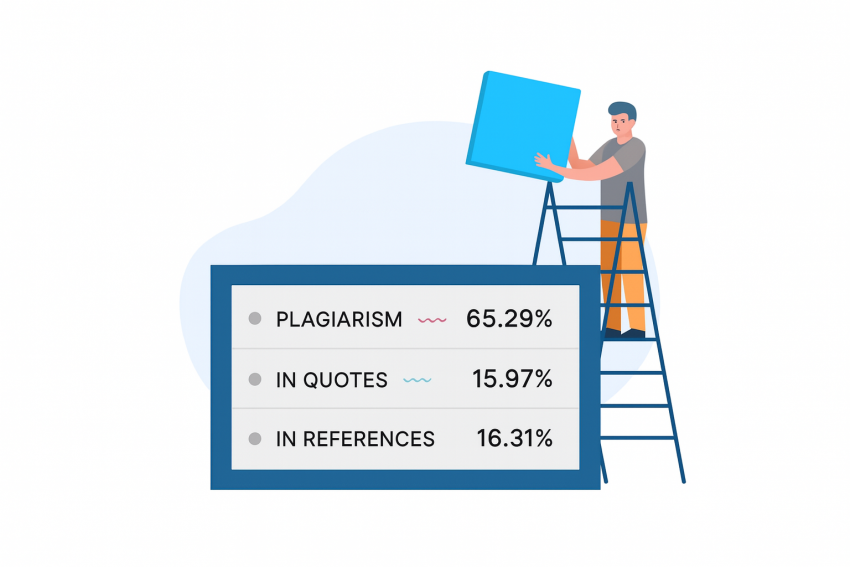

3) How Filters and Settings Change the Number (Quotes, References, Small Matches)

Similarity tools allow configuration that can drastically shift the final percentage without any change to the underlying writing. Understanding these levers helps you interpret the report intelligently.

Excluding quotations.

If quotation marks or block quote formatting are detected, you can exclude those matches from the percentage. This is helpful for literature or humanities essays that intentionally use longer citations. When quotes are excluded, treat the remaining score as the baseline. If it’s still high, the overlap is coming from paraphrased or unquoted text.

Excluding bibliography/references.

Reference entries tend to match across many papers verbatim. Filtering them reduces noise and gives a clearer picture of body-text originality. A paper that reads 22% including references might drop to 10–12% when they are excluded.

Excluding small matches (e.g., under 8–10 words).

Standard phrases and titles can create many tiny, low-value matches. A small-match threshold cleans these up. However, be cautious: patchwriting sometimes creates a chain of small matches that, in aggregate, represent improper paraphrasing. Don’t rely on the number alone after aggressive small-match filtering.

Repository and draft checks.

If the platform stores submissions, a resubmitted draft may match your own previous version and inflate the score. In such cases, most instructors ignore “self-matches,” but you should confirm policy. For group projects, multiple authors may upload similar sections; again, intent and attribution matter more than the raw percentage.

Database breadth.

Some tools emphasize web sources; others have richer academic repositories. A paper may score low in one system and higher in another simply because of coverage differences. That’s another reason fixed thresholds can mislead; a holistic reading of the report is the safer path.

4) Step-by-Step: Interpreting a Report Like an Instructor

Treat the similarity report as evidence to be weighed, not a yes/no test. The following process mirrors how experienced instructors and academic integrity officers typically read these reports.

- Start with filters. Verify whether quotes, bibliography, and small matches are excluded. If not, note how much the percentage drops when they are. The filtered score is your better baseline.

- Scan the top sources. Look for long, contiguous matches from a single source. Ten scattered two-word matches are usually less concerning than one 80-word block that mirrors a paragraph elsewhere.

- Open context windows. Read matched passages in side-by-side view. Ask: Is this a direct quotation with accurate citation and formatting? Or a paraphrase that still follows the source’s structure and key phrasing?

- Check proportion and placement. If most overlap occurs in background or definitions, some similarity may be expected. If it appears in analysis, results, or discussion, the concerns are higher because those sections should reflect original reasoning.

- Evaluate citation quality. Confirm that sources are credited at the sentence or paragraph level, not just in a general bibliography. Proper attribution reduces academic risk even if the percentage remains moderate.

- Consider assignment intent. A literature review, policy brief, or legal memorandum may legitimately incorporate more quoted material than a personal reflection or creative analysis. Align expectations with the task.

- Decide on a response. If overlap looks legitimate but heavy, revise for balance: paraphrase more deeply, synthesize across sources, integrate your own insights, and trim redundant quotations. If overlap includes unquoted copying, rewrite and cite before resubmitting.

A quick illustration helps. Imagine a 1,500-word paper returns 28% similarity. After excluding references and quotes, it drops to 13%. The remaining matches are two paraphrased paragraphs closely following a single source’s structure. Even though 13% sounds acceptable, the pattern still demands revision: the author should reframe ideas, integrate additional sources, and signal attribution within the text.

5) Reducing High Similarity Ethically (Without Over-Paraphrasing)

The goal isn’t to “game the percentage” but to improve originality of thought while honoring sources. Two mistakes are common: over-quoting to play it safe, and mechanical paraphrasing that shuffles words without adding insight. The strategies below reduce similarity by strengthening analysis, synthesis, and voice.

Rebuild from understanding, not from sentences.

Close the source, explain the idea out loud as if to a classmate, and write from memory. Then reopen the text to verify accuracy and add citation. This breaks the tendency to mirror the source’s syntax.

Synthesize across multiple sources.

Instead of paraphrasing one paragraph from one author, combine insights from two or three sources and add your interpretation of how they agree or disagree. Synthesis naturally lowers match density to any single source while raising the intellectual value of your paper.

Use quotations strategically.

Quote when the exact wording carries weight—legal definitions, literary turns of phrase, or technical formulations—and keep those quotes short unless the genre demands otherwise. Surround each quote with your framing and analysis so it supports your argument rather than substituting for it.

Revise structure, not just words.

Patchwriting often keeps the source’s outline. Try changing the order of points, drawing different subheadings, or presenting data in a new format (a short table, a figure, or a brief case comparison). Structural originality is harder to flag and reflects deeper learning.

Document at the right granularity.

Cite where a reader would reasonably expect credit—usually the sentence or paragraph that carries the borrowed idea. General citations at the end do not cure close paraphrase. If several sentences draw on one source, introduce it once and maintain clear signals (e.g., “Smith argues…,” “Building on Smith’s model…”).

Avoid “thesaurus” rewriting.

Replacing words one-for-one keeps the skeleton of the original. True paraphrase involves recasting the concept: define, compare, exemplify, or apply it to a new case. When in doubt, re-explain the claim using your own examples or analogies, then cite.

Calibrate to the assignment.

For a method section in STEM, expect recurring technical language; focus your originality in rationale, interpretation, and discussion. For humanities essays, keep the analysis largely in your words and restrict longer quotes to compelling textual evidence.